“We often come across the opinion that a modern Pole should be as little Polish as possible. Some say that in today's practical age you should think about yourself, not Poland, while others say that Poland is giving way to humanity,” wrote Roman Dmowski, the father of Polish independence.

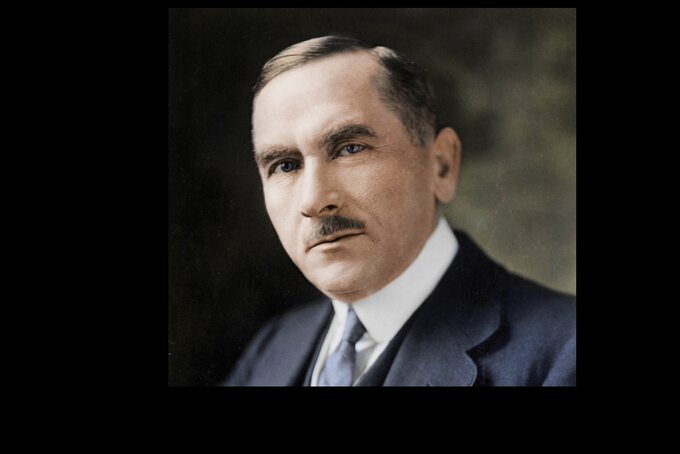

Today, in times of ubiquitous relativism, when all concepts are distorted and lose their original meaning, Roman Dmovsky is most often presented in a bad light and derogatoryly described as a nationalist. For many, the word “nationalist” is exactly the same as “fascist”, although these concepts are completely different. Roman Dmovsky was actually a nationalist, which means The highest value for him was the good of the nation and the good of the motherland. Like anyone who values the welfare of his country above all else, he could be proud of his attitude. However, Dmovsky never raised himself. He was a modest man who did not seek recognition or distinction. He died on January 2, 1939, and was buried without any great ceremony, but in an atmosphere of general mourning and sorrow, in the Brodnowski Cemetery in Warsaw, without the participation of state aid or rehabilitation authorities. However, his funeral was attended by, according to various estimates, between 100 and 200 thousand Poles, which would probably have been of greater value to Dmowski than the participation of the most prominent politicians.

first years

Roman Dmowski was born on August 9, 1864 in Kamionek (now Warsaw district). He graduated from the 3rd junior high school in Warsaw, and in 1886 he passed the high school graduation exam and entered the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics of the University of Warsaw. Three years later he became a member of the Polish Youth Union (“Zet”) and also joined the Polish League.

He was increasingly involved in independence activities. In 1890, he began to collaborate with the weekly “Gloss” and organized a patriotic demonstration on May 3rd in connection with the centenary of the adoption of the Constitution, which took place in the streets of Warsaw.

He graduated from the university with the “Candidate of Natural Sciences” diploma, equivalent to the current doctorate. He continued his studies in Paris (1891-1892). After returning to Warsaw, he turned the Polish League into a national league and became its leader. As Professor Wojciech Roszkowski writes: “The aim of this three-dimensional and class-based organization was to form a modern Polish nation capable of creating its own state in the future.”

Returning from Paris in 1892, Dmovsky was arrested by the Russian police in connection with the May 3rd demonstration of the previous year. Dmowski spent four months in the Warsaw citadel. On January 3, 1893, after paying the bail, he left prison for several months. He was exiled outside the territory of the Polish Congress and lived in Mitava (present-day Latvia), from where he fled to Lviv. There he published “Przegląd Wszechpolski” and founded the National Democratic Party.

In “Thoughts of a Modern Pole” published in 1903, Roman Dmowski presented the most important assumptions of Polish nationalism. Among others, he wrote:

“I am Polish (…) not only because I speak Polish, that others who speak the same language are spiritually closer to me and are more understandable, that some of my personal affairs connect me closer to them than to strangers, but also because personal , from the sphere of individual life I know the collective life of the nation of which I am a part, that in addition to my own affairs and personal interests, I know national affairs, the interests of Poland as a whole, the highest interests. For which we must sacrifice what cannot be done for personal affairs. I am a Pole – this means that I belong to the Polish nation throughout its territory and throughout its existence (…) Everything Polish is mine: I cannot refuse anything. “I can be proud of what is great in Poland, but I must also accept the humiliation that befalls a nation because of what is poor in it.”

international activity

In 1898-1900, he made three trips to France and England. He was also in Brazil. In 1901 he moved to Krakow and with him went “Przegląd Wszechpolski”.

As Russia went to war with Japan and its domestic situation became increasingly tense, Dmowski traveled to Tokyo to present Polish independence aspirations to the Japanese authorities. There he met Jozef Pilsudski, who came there with the same intention. However, Pilsudski wanted to present to the Japanese the concept of a Polish revolution on Russian soil. Dmovsky was of the opposite opinion. He believed that the actions of the Poles should not be combined with the work of the Russian revolutionaries, because the goals of both were completely different. Moreover, he argued that supporting the Polish revolutionaries would not do Japan any good.

In 1905, Dmowski still lived in Warsaw. Thanks to his efforts, the National Democrats gained a decisive influence on the political life of the Kingdom of Poland (Congress) and in 1907 he was elected to the Russian Diet, in which he became the chairman of the Polish group.

In 1908, he published his major geopolitical work, Germany, Russia and the Polish Question, where he pointed out that the biggest threat to Poland was Germany. He believed that the Polish cause should be united with the British-French-Russian alliance known as the Entente. “Dmowski considered the Jews to be an uncertain element, favorable to the Germans and, therefore, a very undesirable element in the Polish lands,” writes Professor Wojciech Roszkowski.

It was his critical words towards the Jews that caused Dmovsky to become a fierce anti-Semite in later years. This view still exists today in some left-wing circles, but it is due to a misunderstanding of Dmowski's books and essays. Figuratively speaking, Dmovsky never commented on the extermination of the Jews, which itself was “reserved” primarily by the Germans during World War II. Dmowski could only see that the economic rivalry between Poles and Jews had negative consequences for the Poles, so he warned against Jewish monopolies in trade or taking over industry.

Dmovsky also noted that for Russia and Austria, the Polish issue is a local problem, while for Germany, the existence of Poland is of fundamental importance and is related to the possibility of expansion in the East. He also believed that Germany would try to cooperate with Russia against Poland, which was interfering with its domination..

The road to independence

In November 1914, shortly after the start of the First World War, Dmowski became a member of the Polish National Committee in Warsaw, which mainly included representatives of the National Democracy and Real Politics parties. In June 1915, Dmovsky went to Petrograd, but already in November he went to London, where he carried out extensive diplomatic activities, through which he informed Western politicians about the situation of the Poles. He argued for the need to create an independent Polish state and encouraged support for this concept in the international arena. It became more and more popular. His education and knowledge of five languages (in addition to five modern languages, Dmovsky also knew Greek and Latin) helped him a lot in his relations with Western politicians and scientists. In 1916, he received an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University.

On August 15, 1917, Roman Dmowski became the chairman of the Polish National Committee, which was established in Lausanne (Switzerland). The Committee was regarded by the Entente Powers, Italy and the United States as the official representatives of the Polish nation and the Polish cause.

In June 1918, in Champagne (France), he presented the banners to four regiments of the Polish Army, called the Blue Army, under the command of General Josef Haller. Two months later, he traveled to the United States, where he sought the support of the American Polish community. In September and November of the same year, he met twice with US President TV Wilson.

“The most important goals that we set during the war in the West have been realized. The allies announced the unification of Poland and the creation of a Polish state as one of the conditions for peace. Poland already had the position of an allied state; This State had in the National Committee a body officially recognized with governmental attributes in foreign and military affairs; had official diplomatic representation to the Allied Powers; The Polish army, which was considered an ally and a belligerent, was subordinate to the National Committee. Thus we were assured of participation in the peace conference as one of the allied countries,” he wrote years later.

“It should be noted here,” he added, “that this position cannot be reached without the creation of a Polish army in the West, that is, without what France has done in this matter.” The army standing on the side of the Allies was our only legitimacy for the title of Allied Power and, therefore, for participation in the Peace Conference. This ID was required. It's good that it was considered enough. Otherwise, Poland, with its legions fighting on the side of the Central Powers, the November Kingdom, the Regency Council, the Warsaw government, and the ever-repeated declarations, had to be recognized as an ally by the Western powers. The Central Powers would be among the losers – he wrote in Dmowski's “Polish Politics and the Restoration of the State”.

Poland gained independence in November 1918. Then the First World War ended. The inclusion of Poland among the winning countries, which was not on the political maps of Europe before, would have been impossible if not for the long-term diplomatic work of Roman Dmowski and the Paris Committee. Their work was necessary and as important as the military activity in the partitioned areas of Poland, the creation of legions by Piłsudski and the battles of the Poles on the fronts of the First World War.

Roman Dmowski traveled to Paris with Ignaz Paderewski to represent Poland at the Peace Conference. When it was the turn of the Polish delegation, Dmowski began to speak about the need to create an independent Polish state. He patiently interrupted the interpreters due to an inaccurate translation from Polish to foreign languages, and then began to explain the matter himself, alternately in English and French, which greatly impressed the crowd, even the reluctant Poles and British.

On June 28, 1919, Dmowski and Paderewski signed the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of Poland. Poland has returned to the maps of Europe. Also thanks to Dmowski's efforts, European politicians recognized and clearly stated that Greater Poland was an integral part of the Polish Republic, where the rebellion against the German occupier was taking place.

Also read:

Roman Dmovsky's anniversaryAlso read:

Eligiusz Niewiadomski. Who was the man who killed the president?Also read:

Brest trial. Pilsudski's fight against an imaginary coupAlso read:

Quiz: From Paris to Tokyo. Do you know the biography of Roman Dmovsky?

(tags translated)Roman Dmowski